The USDA organic standards allow most natural substances in organic farming while prohibiting most synthetic substances. The National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances -- a component of the organic standards -- lists the exceptions to this basic rule. A primary function and responsibility of the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) is to determine the suitability of the inputs that may be used in organic farming and handling and making recommendations for including or removing inputs from the National List.

Blue and Green

Every household needs a good toolbox and a well-stocked first aid kit to deal with unexpected challenges that can’t be handled in the usual way. And so it is with organic agriculture.

Many consumers believe that absolutely no synthetic substances are used in organic production. For the most part, they are correct and this is the basic tenet of the organic law. But there are a few limited exceptions to this rule, and the National List is designed to handle these exceptions. The National List can be thought of as the “restricted tool box” for organic farmers and handlers. Like the toolboxes or first aid kits in our cupboards to deal with critical situations when all else fails, the organic toolbox is to be used only under very special circumstances.

The organic farmer’s toolbox contains materials that have been traditionally used in organic production. By law, they are necessary tools that are widely recognized as safe and for which there are no natural alternatives. This toolbox is much smaller than the “full-toolbox” used in conventional farming.

Organic farmers have restricted access to 27 synthetic active pest control products while over 900 are registered for use in conventional farming.

Organic ranchers have restricted access to 37 synthetic livestock health treatments, while over 550 synthetic active ingredients are approved in conventional animal drug products.

Before organic farmers can use any of these substances, however, they must develop a pest and disease management plan that describes how they will first prevent and manage pests without the use of National List inputs.

The restricted toolbox can only be opened when mechanical, cultural, and biological controls are insufficient to control pests, weeds and disease. This is foundational to organic farming.

The National List is also designed to cover the up to 5% non-organic minor ingredients allowed in organic food processing. These ingredients are essential in organic food processing but difficult or impossible to obtain in organic form, either because the supply is very limited or the ingredient is a non-agricultural, like baking soda, and cannot be certified organic. A total of 67 non-agricultural minor ingredients are allowed in an organic processor’s “pantry,” while the conventional food processor’s pantry is bulging with more than 3,000 total allowed substances.

The restricted toolbox used in organic production and handling represents the best and least-toxic technology our food system has developed.

NOSB regularly reviews the tools in the organic toolbox to assure they still meet the organic criteria set forth in the law. Under the rigorous Sunset process, NOSB and organic stakeholders review the contents of the toolbox every five years to make sure that organic’s allowed tools continue to be safe for humans, safe for the environment, and necessary because of the lack of natural or organic alternatives. There is no other regulation like this in the world.

Now more than ever, organic agricultural practices are needed on more acres to address significant environmental challenges for our planet. Now more than ever, the supply of organic ingredients, particularly grains and animal feed, is falling behind consumer demand. We face the dual challenges of encouraging more farmers to convert to organic and making our food production more sustainable. NOSB’s challenge is to protect the integrity of organic, while at the same time providing producers and handlers with enough flexibility to allow them to comply with organic standards and to also expand organic acreage.

Like the toolboxes and first aid kits of households that are prepared for unexpected emergencies should they arise, the organic toolbox provides the tools to safely meet the challenges of today’s organic world.

Learning from others and compiling a list that works

It took five years for the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB), a group of fifteen public volunteers appointed by the Secretary of Agriculture who represent various sectors of the organic industry, to complete a massive review of the inputs in use by organic producers and processors, and of state, private, and foreign organic certification programs to help craft the final organic regulations.

It was from this extensive research and engagement with everyone in the organic chain, and following thousands of comments to federal regulators, that the National List was compiled, reworked and reworked again, and then officially established on Dec. 21, 2000. The list mirrored most of the standards that organic producers and handlers were already abiding by through the various certification programs of the time, and was formulated to be flexible enough to accommodate the wide range of operations and products grown and raised in every region of the United States.

What are some of the allowable substances on the National List? For crop producers, the list includes things like newspapers for mulch and sticky traps for insect control. For livestock producers, it includes vaccines, an important part of the health regimen of an organic animal for which antibiotics are prohibited, and chlorine for disinfecting equipment. For organic processors, the list includes ingredients essential to processed products that can’t be produced organically, like baking soda, and certain vitamins and minerals and non-toxic sanitizers.

Of course, not all the allowed items on the National List are non-controversial. But all of the substances on the list are required to fulfill three critical criteria as specified by the Organic Foods Production Act: 1) Not be harmful to human health or the environment; 2) Be necessary to production because of unavailability of natural or organic alternatives, and 3) Be consistent with organic principles.

A no-growth trend in synthetics

The first several years of the implementation of the list were a period of fine-tuning, adjustment and just plain learning. Some materials essential to safe organic production had been overlooked and were added, like ozone gas for cleaning irrigation systems and animal enzymes for organic cheese production — both put on the list in 2003.

In 2007, the number of non-organic agricultural ingredients allowed in organic processed products was dramatically tightened. Processed products with the organic label must contain 95 percent certified organic ingredients. Before 2007, the agricultural ingredients that could be used in the remaining 5 percent category were not spelled out; ANY non-organic agricultural ingredient could be used if it was not available in organic form. In 2007, 38 specific substances were defined and added to the National List of non-organic ingredients allowed in a processed organic product. So with the addition of 38 materials to the National List, what had been an unlimited number of non-organic agricultural ingredients allowed in organic processed foods was reduced to a closed list of just several handfuls.

For a decade since 2008, an even greater shift away from synthetics occurred, with just six synthetics added to the list, and a total of 77 during that same time period removed, denied from the list, or further restricted.

A real-life example of a determined individual working within the NOSB system to replace an allowed synthetic material on the National List with a certified organic substitute occurred in 2013. The head of the company, which makes rice-based ingredients that food manufacturers use as alternatives to synthetic ingredients, submitted a petition in 2010 to remove silicon dioxide from the National List since his company had developed a rice-based certified organic alternative to the synthetic. In 2013, the NOSB amended the use of silicon dioxide and weighed in favor of organic rice hulls when available.The no-growth trend in synthetics from 2008-2018 shows a strong preference for the use and development of non-synthetic and organic alternatives.

Enabling organic to grow and preserving the system’s integrity

The system was more arduous and took longer than expected, but it worked. It was proof that the National List has the foresight to include synthetic ingredients when there are no organic or natural alternatives, and thereby enabling the organic industry to evolve and grow, but more importantly, the system provides a method to retire a synthetic substance and implement the organic alternative when it becomes available.

The National List represents a process that is rigorous, fair and one that works. It reflects realistic organic practices, while taking into account current obstacles to ideal production. It encourages public scrutiny, comment and engagement.

Organic food sales in the United States have jumped from slightly more than $18.1 billion in 2007 to nearly $50 billion in 2018. According to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service’s 2016 Certified Organic Survey, the number of certified organic farms in the country totaled 14,217 farms in 2016 compared to 3,000 tops in the mid-1990s. Today, the total number of certified organic operations exceeds 26,000 nationwide.More certified organic farmers, more organic products, more organic processors and handlers, an organic farm-to-table supply chain that is growing every day, but still adhering to a tight set of stringent guidelines—that’s what the National List has made possible.

Our Petitions to Reduce Synthetics and Strengthening Organic Requirements

Acting on extensive feedback and input from its members, OTA filed 3 petitions with the National Organic Program in 2014 to amend the National List of substances that can be used in organic production and processing to reduce synthetics and strengthening the requirement for organic ingredients.

➣ Removing the exemption for synthetic lignin sulfonate in post-harvest handing of organic pears

At the time of the petition (2014), there were two substances on the National List that can be used as floating agents in the handling of organic pears: lignin sulfonate and sodium silicate. As the pear industry modernized its equipment, the use of floating agents declined. The trade association contacted certified organic pear packers and found that those still using a floating agent are using sodium silicate exclusively. Thus, lignin sulfonate fails to meet the criteria that it is essential for organic production, and we petitioned that it be removed as an allowable post-harvest floating agent. In fall 2017, NOSB recommended to remove listing, and the NOP final rule to amend the National List was published on July 6, 2017.

➣ Strengthening the requirement for organic flavors in processed products

Natural flavors are allowed in certified organic processed foods in the 5 percent non-organic portion, provided they are produced without synthetic solvents, synthetic carriers and artificial preservatives. They must also be made without the use of genetic engineering and irradiation. Natural flavors have been included on the National List since it was first implemented in 2002. Since that time, however, many organic flavors have been developed and are being successfully used by many companies. The number of organic flavors in the marketplace has become substantial, so we petitioned (2014) to revise the current listing of natural flavors to require the use of organic flavors when they are commercially available in the necessary quality, quantity or form. In fall 2015, NOSB voted unanimously in favor of the petition, and NOP final rule to amend the National List was published December 27, 2018. The new requirement becomes effective on December 27, 2019.

➣ Protecting the continued production and availability of NOP certified encapsulated dietary supplements

On January 31, 2018, we submitted a petition on behalf of our National List Innovation Working Group to add pullulan to the National List as an allowed non-agricultural, non-synthetic ingredient used in tablets and capsules for dietary supplements made with organic ingredients. The need for this petition is due to a recent interpretation change to classify pullulan as “non-agricultural” instead of “agricultural.” Under the previous interpretation, pullulan was allowed in in the non-organic portion of dietary supplement labeled “made with” organic ingredients, which significantly contributed to the growth of NOP certified supplements. Under the new interpretation, pullulan would be required in certified organic form unless it is added to 205.605(a) as an allowed non-agricultural minor ingredient. Unfortunately, there are no other NOP compliant vegetarian options available for producing NOP certified vegetarian encapsulated supplements, and organic pullulan is currently not commercially available for use in the United States. Thus, if pullulan is not added to the National List, the production of NOP certified encapsulated vegetarian supplements will not be possible. The purpose of the Organic Trade Association’s petition is to protect the continued production and availability of USDA-NOP certified encapsulated dietary supplements, and to support the commercial development of certified organic pullulan. NOSB unanimously passed this petition at the spring 2019 meeting. NOP will need to implement this decision through rulemaking

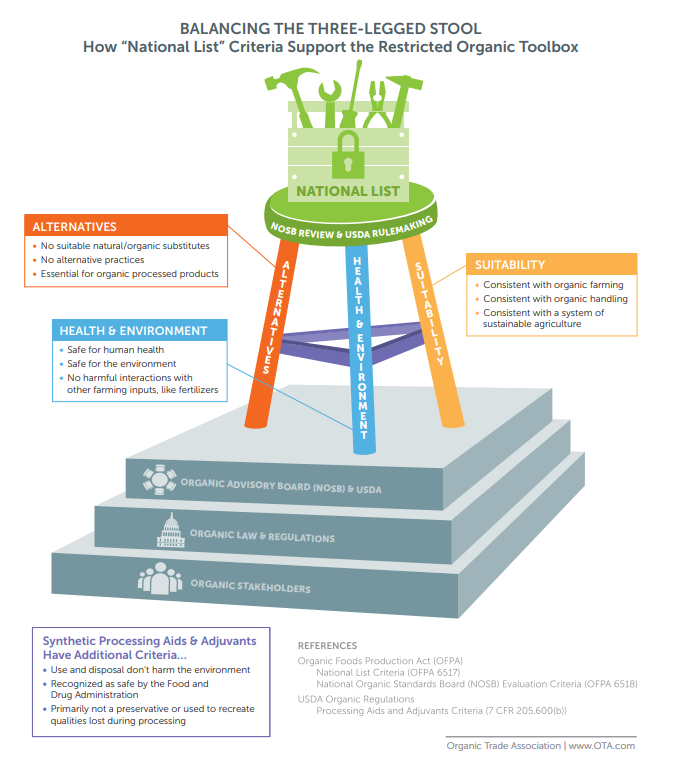

The Organic Toolbox is Supported by a Three-Legged Stool

A primary function and responsibility of the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) is to determine the suitability of the inputs that may be used in organic farming and handling. NOSB was in fact designed by the Organic Food Production Act (OFPA) to advise the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as to which inputs should be allowed. The organic law and regulations specify the evaluation criteria NOSB must use when it makes its recommendation to USDA. The evaluation criteria and review process used by NOSB when voting on the suitability of inputs can be likened to a three-legged stool. The National List, which we often refer to as the “Restricted Organic Toolbox,” is supported by three legs, each one representing criteria to be met for an input to be added or removed. If any one of the three legs is missing, the stool falls over and the action on the input fails. The organic law (OFPA) and the organic regulations include a number of factors NOSB must consider when deciding on the suitability of an input. If one takes a look at the sum of all parts, the conditions that must be met fall into three main clearly stipulated criteria: 1) the input is necessary or essential because of the unavailability of natural or organic alternatives; 2) the input is not harmful to human health or the environment; and 3) the input is suitable with organic farming and handling. These three criteria comprise the three legs of the stool.

Alternatives

Perhaps the simplest of the three main criteria is researching whether there are natural or organic alternatives. The organic law clearly states the National List may allow the use of an input in organic farming or handling if it is “necessary to the production or handling of the agricultural product because of the unavailability of wholly natural substitute products.” The law also states NOSB shall consider alternatives in terms of practices or other available materials. The organic regulations at § 205.600(b) also bring in additional but similar criteria for synthetic processing aids and adjuvants, allowing their use only when there are no organic substitutes and when they are essential for handling or processing. While this leg of the stool is arguably the most simple of the three, NOSB and organic stakeholders have long struggled with this criteria because of the terms “necessary,” “essential,” and “availability.” How much of something is needed to consider it available in the volume needed? What if a natural alternative is available but the quality is not sufficient? What if the alternative works in one region of the country but not another? What if there is an alternative but it’s important to have more than one option? Determining whether there are natural or organic alternatives continues to be more challenging than one might think, and for this particular criteria, NOSB relies heavily on the feedback from organic stakeholders, especially the organic farmers and handlers growing and making organic food, and using the inputs and practices in question.

Human Health and the Environment

The restricted organic toolbox used in organic farming and handling represents the best and least toxic technology our food system has developed. That is exactly how we want to keep it. This principle is bound by the organic law, which states specifically that inputs that otherwise would be prohibited can be added to the National List only if their use is not harmful to human health or the environment. The law also requires the final decision made by USDA to be done so in consultation with the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. To help NOSB advise USDA on this complex topic, the organic law provides NOSB with evaluation criteria to consider in order to explore the toxicity of the input during manufacture, use and disposal, and the potential interactions the input may have with other inputs or within the farming ecosystem. The organic regulations bring in additional but similar criteria for synthetic processing aids and adjuvants that consider the impact their use has on the environment and the safety status under the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Evaluating whether an input may be harmful to human health and the environment is no easy task. Members of the Board represent several areas of the organic sector and hold advanced degrees in different scientific disciplines, but they may lack the expertise or time to adequately address the needs of a petition. It is for this reason NOSB may request the assistance of a third party to evaluate a material. This comes to NOSB in the form of a Technical Review that is made available to NOSB and the public. In addition to the Technical Review, NOSB looks to the scientific experts in the community to provide meaningful input.

Suitability with Organic Farming and Handling

In addition to alternatives, human health and the environment, NOSB must determine the suitability of an input with organic practices. This is arguably the most nebulous of the three criteria, prompting NOSB to pass a guidance recommendation in spring of 2004 that includes a series of questions to assist the Board in its evaluation process. This guidance is now incorporated into NOSB’s Policy and Procedures Manual, and plays a central role in NOSB’s review process.

The questions in the guidance are largely tied to the definition of “organic production” codified in the organic regulations emphasizing practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. Questions are also asked about the influence the input may have on animal welfare, the consistency the input has with items already on the National List and with international standards, and whether the input satisfies the expectations of organic consumers regarding the authenticity and integrity of organic products.

The third leg of the stool can be viewed as the “equalizing” leg of the stool, helping NOSB balance its evaluation of alternatives, human health and the environment. For example, if the information provided on human health raises some concerns, but the science is insufficient, or alternatives are available but they do not work in all regions of the country or in all types of products, NOSB will evaluate how suitable the input is overall with the foundations of organic production and handling. One leg of the stool may not fail the criteria altogether but it might be shorter than another leg, creating concern … and a tilted stool. The suitability criteria help NOSB adjust and balance the stool. Similarly, the input may pull up short in the suitability department, causing the stool to topple. Either way, NOSB’s final recommendation must deliver a balanced three-legged stool that firmly supports the restricted organic toolbox.

The Three-Legged Stool Stands on a Solid Yet Dynamic Foundation

The three-legged stool holding up the National List stands on a firm foundation made up of organic stakeholders, the organic law, the organic regulations, NOSB and USDA’s National Organic Program. The organic law was created in response to the needs of organic stakeholders, and the law in turn created NOSB and the USDA organic regulations. Today, the entire process we use to shape the National List continues to be powered and driven by stakeholders throughout the supply chain and the organic community. The National List criteria are tough, the process is rigorous, the discussion and decisions are thoughtful and transparent, and everyone is welcome.

Leveraging Our Success

As the sector evolves and grows, so does its contribution to more sustainable approaches in food production. Organic is a leader in finding ways to effectively manage agricultural systems by integrating cultural practices such as crop rotation, biological practices like introducing beneficial insects and increasing microorganisms in the soil, and mechanical practices such as tractor cultivation and hand weeding. Organic is also a leader in developing natural and organic farm inputs and food ingredients.

For the organic sector, innovation is a necessity. The strict requirements of organic regulations and the very limited toolbox producers and handlers have to work with make creativity and innovation absolutely essential to succeed. Our success, in turn, depends on biological farming practices and healthier soils that help mitigate climate change, and on a label consumers trust and are increasingly seeking out. This has practitioners from all sides looking over the fence to see what they can learn.

The challenge we face is keeping up with demand, not only on the production side, but also on the research and extension side. Over the years, despite the growing demand for organic, investment in organic research has lagged dramatically behind the funds devoted to research for conventional agriculture. Organic’s growing success in developing effective alternatives, however, has put today’s organic sector in an advantageous position. Organic has the opportunity now to further leverage our contributions to creating better farming practices and a healthier environment, and to build support for specific research that will benefit the entire agricultural sector.

Lessons Learned

The National List process requires organic farmers and processors to be innovative, tenacious, and to embrace new ideas and blaze new trails. The process requires organic stakeholders to be proactive and on constant watch to discover or develop organic or natural alternatives to replace the synthetic materials now allowed in organic food production. But the path to developing natural and organic alternatives is not easy, it is not cheap, and it doesn’t happen overnight.

The recipe for successfully developing National List alternatives includes a tremendous public-private effort to foster the adoption of new techniques and inputs and develop new supply chains. In 2015, the Organic Trade Association formed the National List Innovation Working Group consisting of members interested in investing in applied research to identify alternatives to materials currently on the National List including organic, natural, or more compatible synthetics. The group realized that in order to proactively remove materials from the National List, it would take time, money, involvement and collaboration with public and private research institutions and extension personnel. The experience to-date of the group combined with other lessons learned from National List inputs, such as antibiotics for tree fruit, methionine for poultry and celery powder for cured meat, have created an extremely helpful model that can be used to help develop organic and allowed natural alternatives.

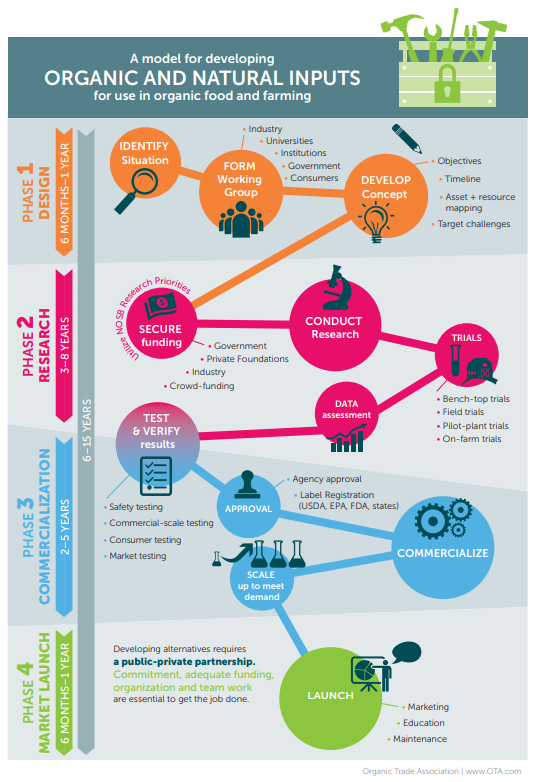

A Model for Developing Organic and Natural Alternatives

The process for developing natural and organic farm inputs and food ingredients can be viewed as a fourphase intensive participatory process: 1) Design; 2) Research; 3) Commercialization and 4) Market Launch. The process on the short end normally takes at least six years. On the upper end, it can take 15 years or more. At a minimum, it takes more than five years.

1) Design: The design of a project sets the stage for success or failure. During this process, the situation and need are identified, a working group with all of the essential partners including industry, universities, government, institutions and consumers is formed, and the project concept, goal and objectives are developed. A key activity at this stage is something known as “asset and resource mapping,” an activity often undertaken in food systems planning, where the complexities of the supply chain are accounted for and the available resources are mapped by region. This creates a visualization of what is available and what is still needed in product and partner supply. The design of a project can take from six months to a year.

2) Research: The research phase is the greatest hurdle in the process, and it will not advance without adequate support and funding. For the organic sector, the funding options are limited but, thankfully, some funds are available through USDA, private foundations, industry donations and other private efforts. Simply securing the funding typically takes a couple years or more. A good starting point can be a planning grant through the Organic Research and Extension Initiative (OREI) under USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. A $50,000 planning grant provides the dollars often needed to complete the asset and resource mapping process that will provide the information and data needed to submit a grant for a full $2 million OREI grant. The research phase takes an additional two to five years at least to carry out bench-top trials, field trials, and/or pilot-plant trials as well as conduct data collection and assessment. Research trials then need to be scaled up to on-farm or commercial-scale testing. Results must be tested and verified, and if found to be successful at the research level, the commercialization process may start.

3) Commercialization: The time it takes to commercialize a farm input or new ingredient is often underestimated. There are significant time and resources that must be spent on additional commercial scale validation, followed by consumer, market and safety testing. Materials on the National List cannot be replaced overnight. New farm inputs or food ingredients must also undergo agency approval and label registration that can take two to three years. Agency support of organic interests is critical at this point. The organic sector can weigh in during this time, emphasizing the importance of prioritizing agency approval, and help to shorten these approval timelines. Once the testing and agency approval are granted, the product must be scaled up to meet market demand. This will ultimately determine the commercial availability of an ingredient or product.

4) Market Launch: Lastly, there is a necessary a period of education and experience for growers and handlers to refine their use of a new material in the diverse settings and environments encountered in commercial settings. As in the case of organic tree fruit growers adopting new materials and practices to prevent fire blight, a significant amount of education and outreach was necessary to convince producers to adopt these alternatives when faced with this devastating plant disease. Growers and handlers have to be confident the alternatives will work. Also, consumers must be willing to accept the new food ingredient in their organic products. The consumer commitment to organic is based on trust that the organic product is the best choice, and that trust has to hold true for any new organic ingredient or product. The process of moving from concept of an alternative ingredient or input, and then to proving its efficacy and integrating or implementing its use into an organic production or handling system represent a multiyear effort that rarely occurs in a timeline shorter than five years.

Communicating with Policy Makers: A Call To Action

Successfully developing alternatives to the National List requires time and significant funding. To strengthen the organic sector’s ability to defend and solicit funds for research that benefits organic production and handling, organic needs to have a voice at the table, and be represented on USDA and other applicable federal research boards and committees.

The organic sector can work with USDA and other federal agencies to ensure fair representation on appropriate research boards by identifying and bringing forth qualified nominees for those boards. Our goal is that all USDA appointed research boards include at least one member representing the interests of organic.

The organic sector has specific and unique research needs regarding production and organic regulatory compliance, and federal agencies need to respond to those needs with the appropriate policies. Government agencies (particularly USDA) need to include organic production as a component of its studies comparing the effects of different agricultural production systems when appropriate (e.g., investigation of climate change adaptation practices). Organic production models provide alternative solutions to current agricultural challenges. We encourage USDA to increase its efforts to develop diversity in research and alternatives for all producers and handlers.

Great strides have been made in the organic sector, but the work is not done. Organic stakeholders have to continue advocating, working, pressing and staying engaged in the process to enable organic to reach its full potential. The Organic Trade Association encourages everyone in the organic sector to help make sure the U.S. Department of Agriculture fulfills its leader’s directive. In this regard, we urge NOSB to draft a letter to USDA requesting mandatory organic representation on USDA research boards and committees.

National List Resources

OTA Resource: The Restricted Organic Toolbox OTA Resource: Get To Know Your National List OTA Resource: National List Criteria OTA Resource: Developing Alternatives OTA’s Fact Sheet on the National List

Sunset Review Process Material Review Organizations Current National List (eCFR)